Get a free book sample

Fill in your information and the book will be sent to your email in no time

Image: 3D illustration of Clostridium tetani, the agent of Tetanus

There’s an urban legend about Tetanus shots. Many people feel you need them only when you step on a rusty nail or if a splinter pokes you. Like any good myth, there is a tiny bit of truth attached to it. Yes, stepping on a nail is a good reason to get a Tetanus shot – but not because of the rust. Once your skin barrier is ruptured, bacterial spores from contaminated items can easily enter your body.

The truth is there are many ways to get Tetanus. Spores of the bacteria that cause infection development, Clostridium tetani, are commonly found in the soil, dust, intestines, and feces of several household animals, herbivores, and even humans. However, it does not spread from one person to another. The best way to control infections is to prevent them from occurring entirely.

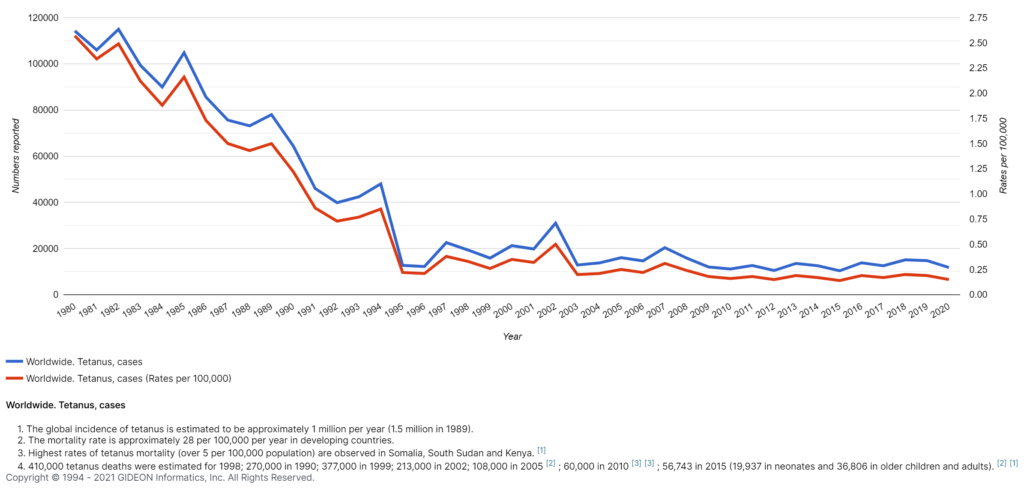

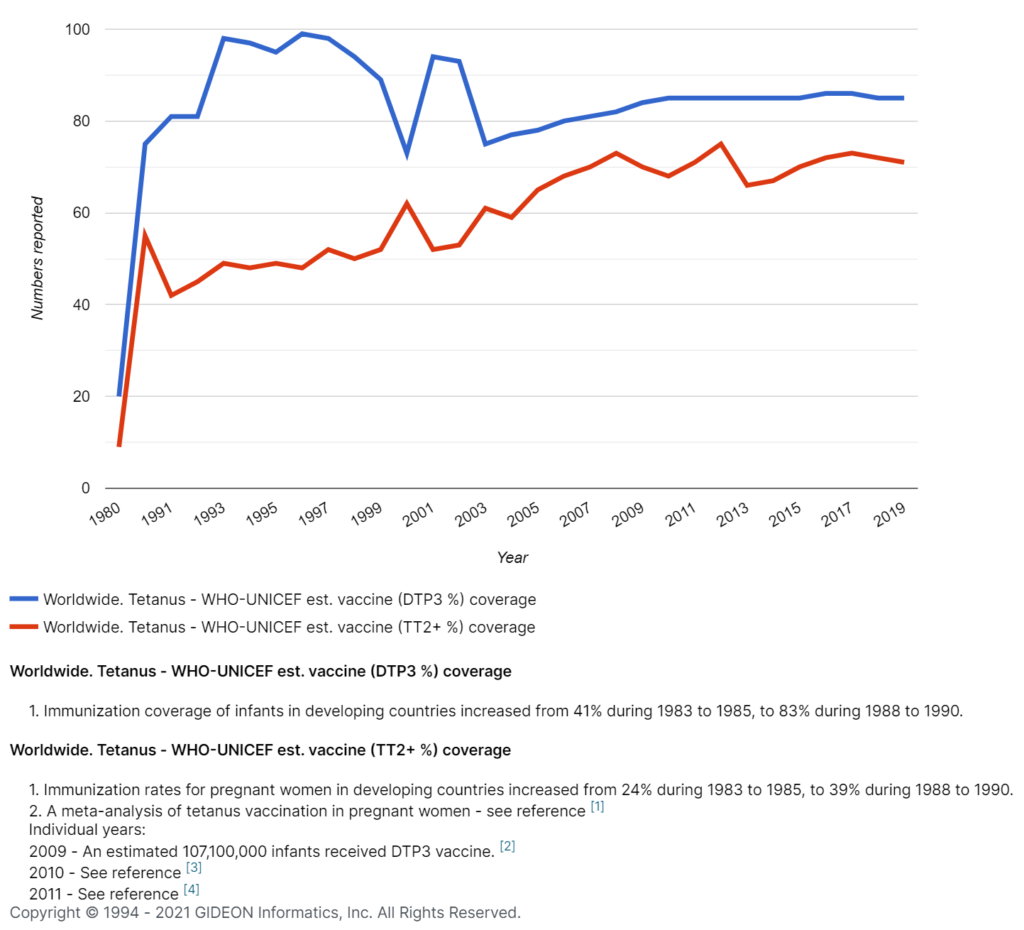

Worldwide, cases have declined rapidly due to mass immunization drives by various governments and public health agencies. However, Russia recently reported its first case in nearly two decades in September 2021 [1]. In India, a 12-year-old boy recently survived a severe case [2]. He had not been vaccinated against it. In Northern Kazakhstan, a 53-year-old man died due to Tetanus, and it is not known if he was vaccinated [3].

One potential reason for these new reports of this highly preventable infection is COVID-19. In July 2020, WHO and UNICEF warned of disruptions to life-saving immunization services across the world due to the pandemic. Healthcare workers and social workers have been unable to follow standard vaccination schedules for many reasons, including:

Before the pandemic, two notable outbreaks occurred in Indonesia during the devastating tsunami in 2005 and an earthquake in 2006. People hurt in disasters are, in general, at a much higher risk of getting infected. In certain parts of Indonesia, a lack of adequate transportation, access to health facilities, and awareness about protocols led to many people dying. Another instance of an outbreak was after the 2005 earthquake that struck Pakistan [4].

Image: Worldwide Tetanus cases and rates, 1980 to 2020. Copyright © GIDEON Informatics, Inc.

Tetanus is one of the deadliest microbial toxins. It is caused by the bacteria Clostridium tetani and has a high fatality rate. Approximately 10-20% of cases are fatal.

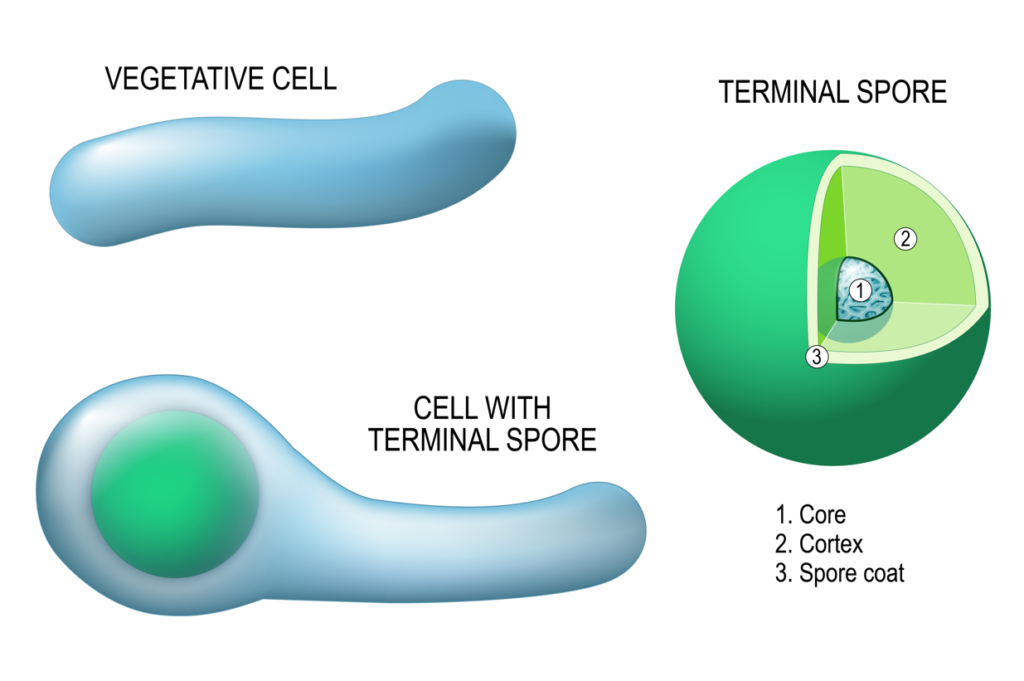

It is also commonly known as lockjaw. Spores of the bacterium, Clostridium tetani, enter our bodies and spread all over the nerves in the central nervous system. The spores produce a toxin called tetanospasmin that blocks nerve signals from the spinal cord to the rest of the muscles. The condition is also commonly known as lockjaw because it often causes severe muscle spasms in the jaw and neck, as well as stiffness, though it may spread to the rest of the body.

Other symptoms are fever, sweats, a rise in blood pressure, and an elevated heart rate. A common complication of Tetanus is when vocal cords begin to spasm, causing breathing difficulties. Infected individuals can also break their bones or spines based on the severity and frequency of convulsions caused by the disease[5].

Tetanus disease spores cannot be killed easily. They are found everywhere and can resist extreme conditions like high heat and strong disinfectants. They can remain inactive but infectious for more than 40 years.

Clostridium tetani is an anaerobic bacterium; it does not live or grow in the presence of oxygen. As a result, there is a higher risk of infection with injury sites that do not receive a strong oxygen supply. This includes deep wounds, burns, needle punctures, and surgical procedures performed without adequate hygiene protocols.

While infection can have serious effects, it is now rare in most developed countries. The United States reports an average of 20 cases per year, mostly in unvaccinated individuals. Though most cases are found in developing countries, many of them now maintain rigorous vaccination programs and made great strides in eliminating or minimizing the incidence of disease. Anyone can get infected, but children and newborns (when infected are known to have neonatal tetanus) are the most susceptible.

Image: Clostridium tetani. Anatomy of the cell with terminal spore, and vegetative cell. Structure of the terminal spore: core, cortex, and spore coat.

The incubation period for Tetanus is anywhere from three to twenty-one days, with an average of ten days. The incubation period varies based on how far the injury site is from the central nervous system. Symptoms can last for weeks and even months. They are higher in unvaccinated individuals and older people for whom immunity is lowered.

There is no cure for the disease, but the vaccine is highly effective in preventing infection. Once infected, however, symptoms are managed until the effects of the toxin diminish. Chances of survival are lower if muscle spasms develop within five days of getting infected.

There are no blood or laboratory tests to diagnose Tetanus. The most common initial symptom is ‘trismus’ or lockjaw due to facial muscle spasms.

Tetanus can be confused with certain other conditions, which makes it more important to educate frontline clinicians about confirming their own initial assessments either with experts or a platform like GIDEON that factors epidemiology data into differential diagnosis.

Tetanus is considered a medical emergency, and hospital care is required. Treatment is often medication called Tetanus Immune Globulin (TIG), also known as an antitoxin. It is usually administered as a preventive measure for high-risk wounds and injuries. It is also part of the treatment protocol, together with medicine. These medicines include muscle relaxants and antibiotics like penicillin. When required, proper wound cleaning and debridement are also essential to minimize the risk of infections. Patients with difficulty swallowing may also need a breathing tube or ventilator [6].

The best prevention is to ensure newborns, children, and adults receive their Tetanus vaccine doses according to the recommended schedule.

Vaccines for the disease are often combined with those for other diseases:

It is important to note that vaccines do not offer lifetime immunity. Many people may need booster shots to continue receiving protection against Clostridium tetani. Additionally, building awareness about improved infection control measures for childbirth, surgery, and other medical protocols in developing and under-resourced nations can make a difference.

Image: WHO-UNICEF estimated vaccine coverage of Tetanus graph, 1980 – 2019. Copyright © GIDEON Informatics, Inc.

GIDEON is one of the most well-known and comprehensive global databases for infectious diseases. Data is refreshed daily, and the GIDEON API allows medical professionals and researchers access to a continuous stream of data. Whether your research involves quantifying data, learning about specific microbes in history or present studies, or testing out differential diagnosis tools– GIDEON has you covered with a program that has met standards for accessibility excellence. You can also review our eBooks on Less-Common Nematodes, Miscellaneous Animal Bite Infections, New World Phleboviruses, and more. Or check out our global status updates on countries like Guyana, Luxembourg, Monaco, and more!

| [1] | Outbreak News Today, “Russia: First Tetanus case reported in Sverdlovsk in nearly two decades,” 19 09 2021. [Online] [Accessed 29 09 2021]. |

| [2] | Times of India, “12-yr-old with rare Tetanus survives at GMCH after 37 days on ventilator,” 17 09 2021. [Online] [Accessed 29 09 2021]. |

| [3] | Outbreak News Today, “Tetanus death reported in Northern Kazakhstan,” 4 09 2021. [Online] [Accessed 09 29 2021]. |

| [4] | New York Times, “Twenty-two Tetanus deaths reported in Pakistan quake zone,” NY Times, 27 10 2005. [Online] [Accessed 29 09 2021]. |

| [5] | H. Bjørnar, “Tetanus: pathophysiology, treatment, and the possibility of using botulinum toxin against Tetanus-induced rigidity and spasms.,” Toxins (Basel), vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 73-83, 2013. |

| [6] | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Tetanus for Clinicians,” CDC, [Online][Accessed 29 09 2021]. |