The Spanish Flu Pandemic: A History of Outbreaks

–

When Did the Spanish Flu Start?

The Spanish Flu began in 1918, towards the end of World War I. The disease is believed to have originated in the United States and France — and not Spain, as one might assume from the name.

Why Was the Disease Called the Spanish Flu?

The flu was named so because, in 1918, most of the reported cases and science came from Spain [2]. Remaining neutral during the war, Spain felt free to publish its disease reports. However, the US and many other European countries like Germany, the UK (formerly Great Britain), and France suppressed reports of the virus to maintain public morale. Many other names are used to refer to the Spanish Flu, including:

- The Spanish influenza pandemic

- 1918 influenza pandemic

- Great influenza epidemic

- The purple death

- Spanish Lady

- The three-day fever

- Blitzkatarrh (by Germans)

- Flanders Grippe (British soldiers)

To paraphrase Shakespeare: the Spanish flu, by any other name, was just as destructive.

Where Did it Start?

It is one of the deadliest pandemics in the history of humankind [3,4]. Although initially, the severity of the disease was mild, future waves were lethal [4]. Unlike other influenza viruses, it affected people aged 15 to 45-year-olds the most [5].

While there is some debate about where the first Spanish Flu outbreak began, two locations were identified as the virus’s origins. The first was in the city of Kansas in the United States. The virus is believed to have originated near an army camp and then made its way to Europe, with thousands of young American soldiers being shipped overseas for war [6].

The second theory proposes that this flu originated in Etaples, France, at a British training camp for soldiers. Apart from crowded quarters housing over 100,000 soldiers, the base had several hospitals catering to sick and wounded soldiers — breeding grounds for disease [6].

Waves of Spanish Flu Outbreaks

There were three waves of outbreaks:

- First wave: Spring 1918

- The first outbreak was detected in March 1918 in Fort Riley, Kansas, at Camp Funston, a US Army training camp. As hundreds of American soldiers traveled to Europe to fight in WWI, they carried the virus, spreading it all over Europe. This wave was relatively mild, but that was about to change.

- Second wave: Fall 1918

- The virus mutated over the summer of 1918, and infections began to skyrocket in August and September of that year. Symptoms in infected individuals got worse and included severe pneumonia, fever, hemorrhaging, and lung damage.

- The pandemic reached its peak during this time. Two-thirds of all the deaths from this flu occurred around October to December 1918. In the United States, Philadelphia had the highest death rate — it didn’t help that the city organized a huge gathering called the ‘Liberty Loan Drive Parade’ to support the war effort. Unfortunately, the event was a breeding ground for the spread of the newly-mutated influenza virus, and its effect was swift.

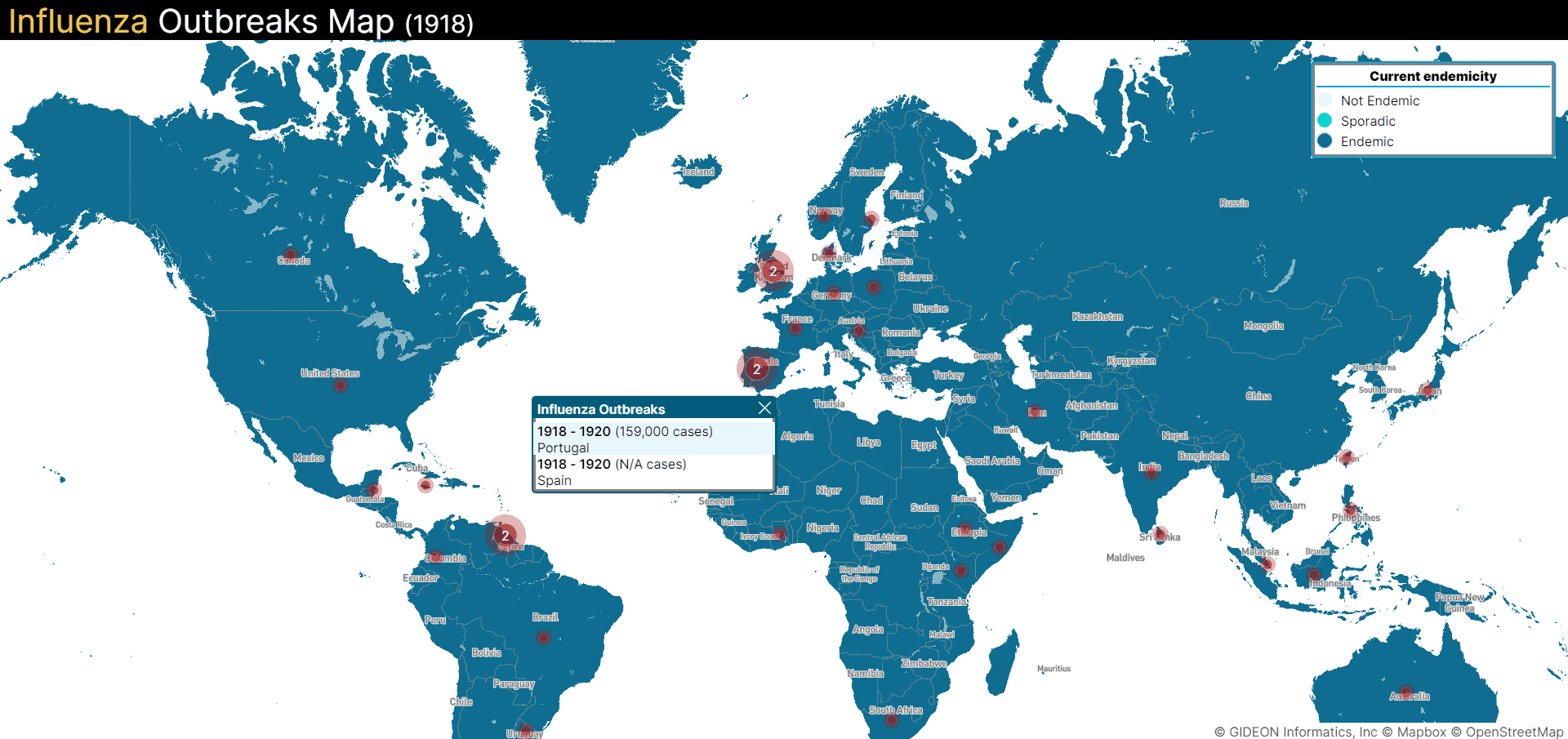

- Almost 200,000 people attended the ill-advised parade with marching bands and floats. Within three days, hospitals were overflowing with sick and dying patients. Many doctors and nurses had been sent overseas, leaving fewer healthcare professionals back home to fight the second war against the infectious disease at home. The pandemic severely impacted many countries worldwide, including the US, Mexico, the UK, France, Germany, India, China, and more. Infections spread far and wide and even decimated over 20% of the population in island nations such as Western Samoa [4,6].

- Third wave: Winter 1918

- The third wave of the pandemic began in October 1918 and continued through the Spring of 1919. This wave was not as severe as the second wave but did take many lives. By the time the third wave hit, people were tired of quarantines, mask mandates, and social distancing measures. These pandemic influenza preparedness measures were very important steps in influenza virus science and also led to the creation of influenza risk assessment and other flu pandemic precautions. However, many were furious that public spaces and businesses were closed. To appease everyone, public health officials began lifting precautionary measures; some even declared the pandemic over prematurely. In America, many people returned to normalcy and crowded spaces like movie theatres, shops, and more. As a result, the death toll continued to mount as the Spanish flu killed more of those infected.