Get a free book sample

Fill in your information and the book will be sent to your email in no time

Image: Brugia malayi in blood, a roundworm nematode, one of the causative agents of lymphatic filariasis, 3D illustration showing the presence of sheath around the worm and two non-continuous nuclei in the tail

Lymphatic Filariasis, commonly known as Elephantiasis, is considered a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD). This is unfortunate because the disease is the second leading cause of permanent and long-term disability in the world! [1] As of 2019, it continues to be a threat to over 859 million people in over 70 countries.

Like other Neglected Tropical Diseases, it is endemic to low-income regions of the globe that deal with poor water quality, sanitation, and limited access to healthcare. India accounts for 47% of chronic Filariasis and 39% of the at-risk population [2]. The good news is that it is considered “potentially eradicable” and can be prevented through timely treatment. Disease spread can be controlled through mosquito control measures [3].

But what is this disease? What are the different types of Lymphatic Filariasis? Where is it found? How do we treat it?

Lymphatic Filariasis is an infectious tropical disease caused by parasitic roundworms (nematodes) transmitted by mosquitoes. The disease is named after the family of worms, Filariodidea.

The disease affects the lymphatic system – the intricate network in our body that is an integral part of our circulatory and immune systems. It can cause severe swelling and disfigurement; body parts may swell up to abnormal proportions.

Because of the resulting disfigurement and pain, people suffering from Lymphatic Filariasis often face social isolation and loss of income, leading to mental health issues and greater poverty.

In recent years, the World Health Organization (WHO) and high-risk countries, have organized mass treatment of all eligible people against Lymphatic Filariasis. This type of preventable chemotherapy has successfully proven to help stop the spread of infection [4].

There are three types of Lymphatic Filariasis based on the type of pathogen that causes the disease – Bancroftian, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori.

1. Bancroftian Lymphatic Filariasis

Bancroftian Lymphatic Filariasis comprises 90% of all lymphatic filariasis cases around the world. It is caused by a worm called the Wuchereria bancrofti (W. bancrofti). The earliest descriptions of Bancroftian Filariasis dates as far back as 600 B.C. in India! The disease is named after the dynamic father-son duo of eminent Australian doctors and parasitologists Dr. Joseph Bancroft and Dr. Thomas Bancroft.

The W.bancrofti worm needs two hosts to complete its life cycle. It sexually reproduces in humans and matures in Anopheles mosquitoes. This has a long incubation period of anywhere from 5 – 18 months, making it harder to detect early without preventive care in high-risk areas.

Image: Advanced Elephantiasis – a patient in the Philippines

2. Brugia malayi

The Brugia malayi is a type of roundworm that relies on Mansonia and Aedes mosquitoes as vectors. The adult worms that grow in a human’s lymphatic system are similar but smaller to the W.bancrofti. Human infection often includes swollen lymphatics of the neck, groin, or axilla.

Brugia malayi is endemic to South and Southeast Asia. It usually takes many bites from mosquitoes carrying the Brugia malayi pathogen before a human can be infected. This is why high-risk countries need to improve their sanitation and water quality standards. Additionally, they need to periodically perform proactive mass drug treatments proven to be effective against Lymphatic Filariasis.

3. Brugia Timori

Brugia timori is a roundworm that uses the Anopheles mosquito as its vector. The life cycle of this worm is similar to the W.bancrofti and Brugia malayi. The prevalence of this variety of Lymphatic Filariasis is much less compared to the other two. It is usually limited to Timor and the Lesser Sunda archipelago of southeast Indonesia [5].

A review of Brugia timori on the GIDEON database shows that the number of people infected by Brugia timori is estimated to be less than 800,000.

There are many similarities in symptoms of the three types of Lymphatic Filariasis, but differences do exist. Below is a dynamic comparison chart generated by the GIDEON platform for symptoms of W.bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori infections.

Image: Comparison chart for clinical findings related to Bancroftian, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori Lymphatic Filariasis. Copyright © GIDEON Informatics, Inc.

Treatment for Lymphatic Filariasis is concentrated around large-scale chemotherapy known as mass drug administration (MDA). WHO recommends an annual dose of preventive chemotherapy drugs to high-risk populations:

In countries without onchocerciasis (river blindness, another type of Filariasis), WHO also recommends ivermectin (200 mcg/kg) together with diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) (6 mg/kg) and albendazole (400 mg) in certain settings.

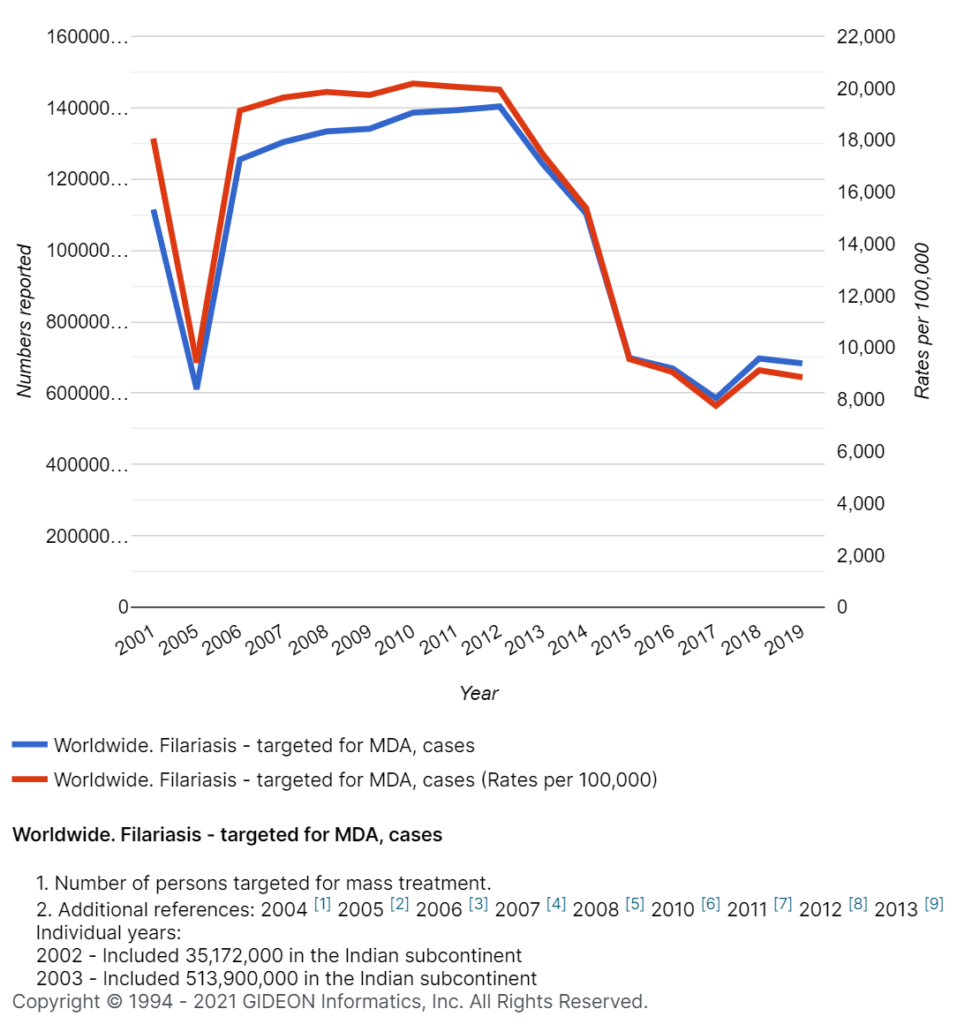

Image: The global number of people targeted for mass drug administration (MDA) for Filariasis. Copyright © GIDEON Informatics, Inc.

Some studies have shown that Doxycycline administered over six weeks significantly improved the severity of Lymphatic Filariasis in patients with and without active infection. Doxycycline worked to revert or halt the progression of early stages of Lymphatic Filariasis (1-3), not later ones [6]. Doxycycline is an antibiotic often touted as a ‘wonder drug’ because it can kill various pathogens in situations where other antibiotics may fail, like for malaria and against Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for the Plague. The effects of Doxycycline last for a while, so it is effective for both treatment and prevention.

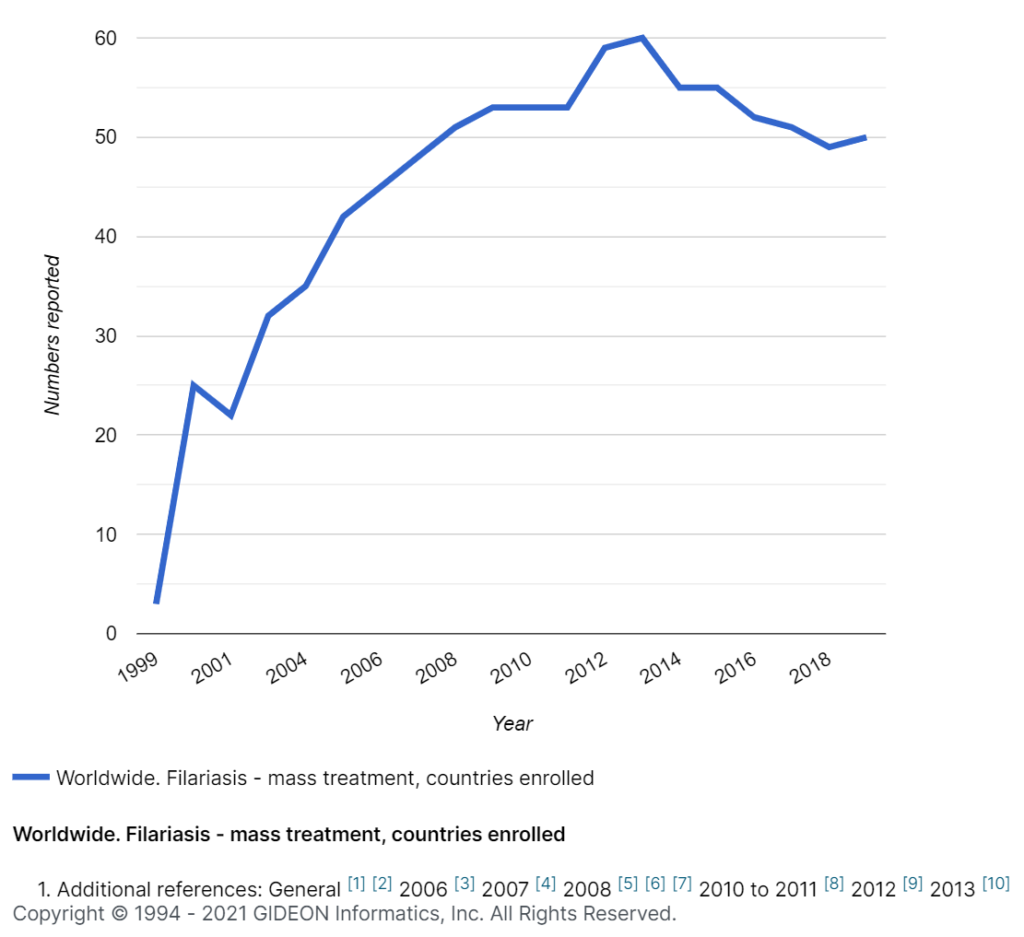

Image: A graph illustrating countries enrolled on mass treatment programs for Filariasis. Copyright © GIDEON Informatics, Inc.

Apart from MDA methods, stringent vector control is essential to eliminate or reduce the incidence of Lymphatic Filariasis. Studies show that vector control after MDA is extremely effective in reducing the resurgence of the disease and preventing spread. Vector control includes bed nets and the regular spraying of insecticides to prevent mosquito bites [7].

Additionally, more researchers are beginning to incorporate the epidemiological impact of infectious diseases in their studies. For example, over 20 research papers used GIDEON epidemiology data on infectious diseases as part of their parasitology-focused papers in the past three years alone. This is a welcome trend that can raise awareness about neglected tropical diseases, preventive measures and help drive much-needed resources towards mitigating the devastating effects of these parasites.

| [1] | CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), “Hygiene-related diseases: Lymphatic Filariasis,” 2 08 2016. [Online] [Accessed 15 09 2021]. |

| [2] | GIDEON Database (Global Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Online Network), “Filariasis – Bancroftian worldwide distribution,” GIDEON Informatics, Inc, 2021. |

| [3] | PAHO (Pan American Health Organization), “Paho.org,” PAHO, [Online] [Accessed 15 09 2021]. |

| [4] | WHO (World Health Organization), “who.int,” WHO, 18 05 2021. [Online][Accessed 15 09 2021]. |

| [5] | P. Fischer, T. Supali and R. M. Maizels, “Lymphatic filariasis and Brugia timori: prospects for elimination,” Trends Parasitol, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 351-5, 2004. |

| [6] | S. Mand, A. Y. Debrah, U. Klarman, L. Batsa, Y. Marfo-Debrekyei, A. Kwarteng, S. Specht, A. Belda-Domene, R. Fimmers, M. Taylor, O. Adjei, and A. Hoerauf, “Doxycycline Improves Filarial Lymphedema Independent of Active Filarial Infection: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Clin Infect Dis., vol. 55, no. 5, p. 621–630, 2012. |

| [7] | E. L. Davis, J. Prada, L. J. Reimer and T. D. Hollingsworth, “Modelling the Impact of Vector Control on Lymphatic Filariasis Programs: Current Approaches and Limitations,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 72, no. Supplement_3, p. S152–S157, 2021. |