Cat Scratch Disease (CSD)

Cat scratch disease is also known as cat scratch fever (CSD) or subacute regional lymphadenitis. It is the most common Bartonella infection. The disease is caused by the species Bartonella henselae and infects the lymph nodes near the sites of cat scratches, causing them to swell. It is a common source of swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) in children and teenagers. On occasion, flea or tick (arthropod) vectors can directly transmit CSD to humans [3].

History

Cat scratch disease was first described in 1931 by Dr. Robert Debré. The doctor observed regional lymph nodes swelling after cat scratches. Twenty years later, he published his report on CSD, which officially recognized the infection as a clinical condition [4]. However, B. henselae, the causative agent, was not identified until the 1990s through PCR amplification [5].

Epidemiology

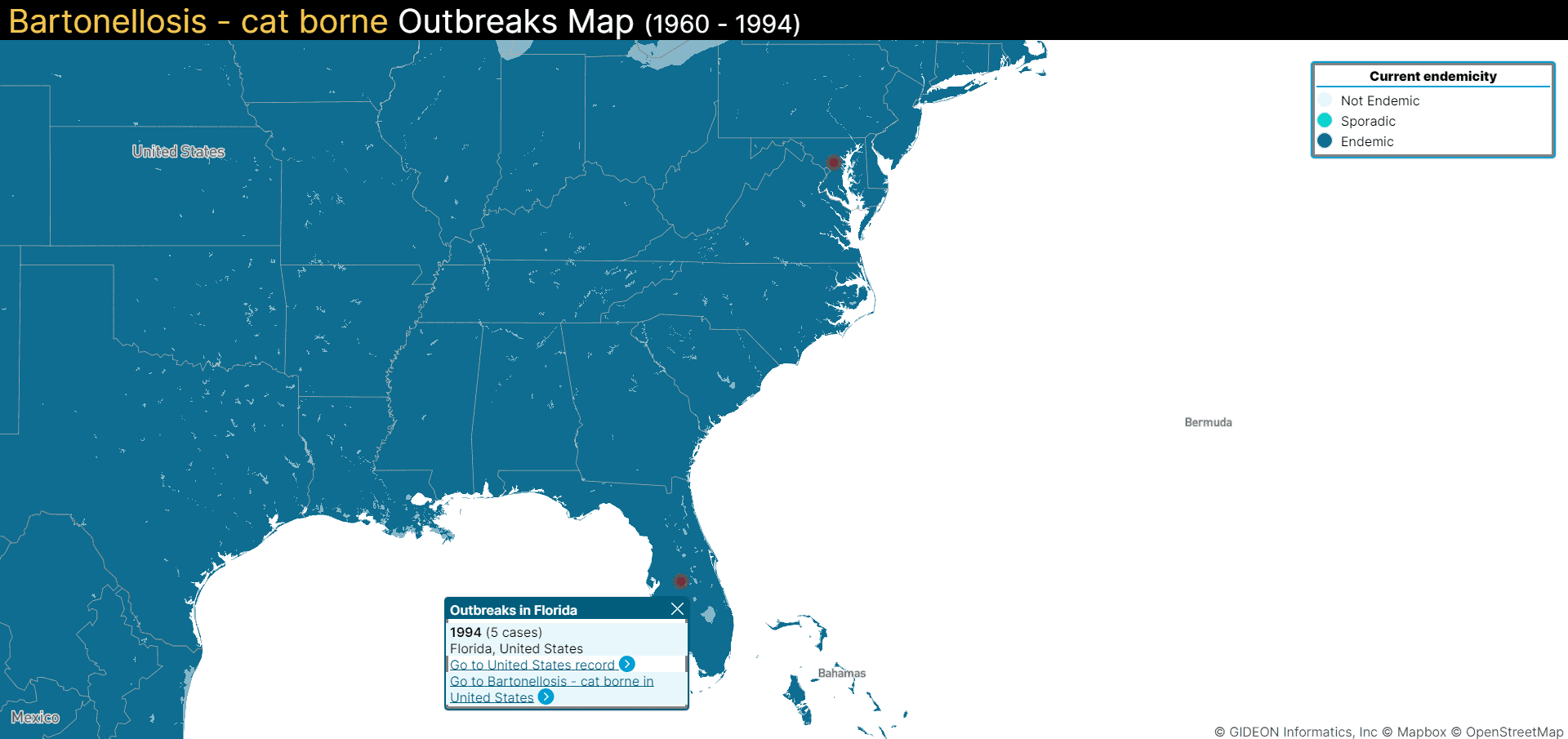

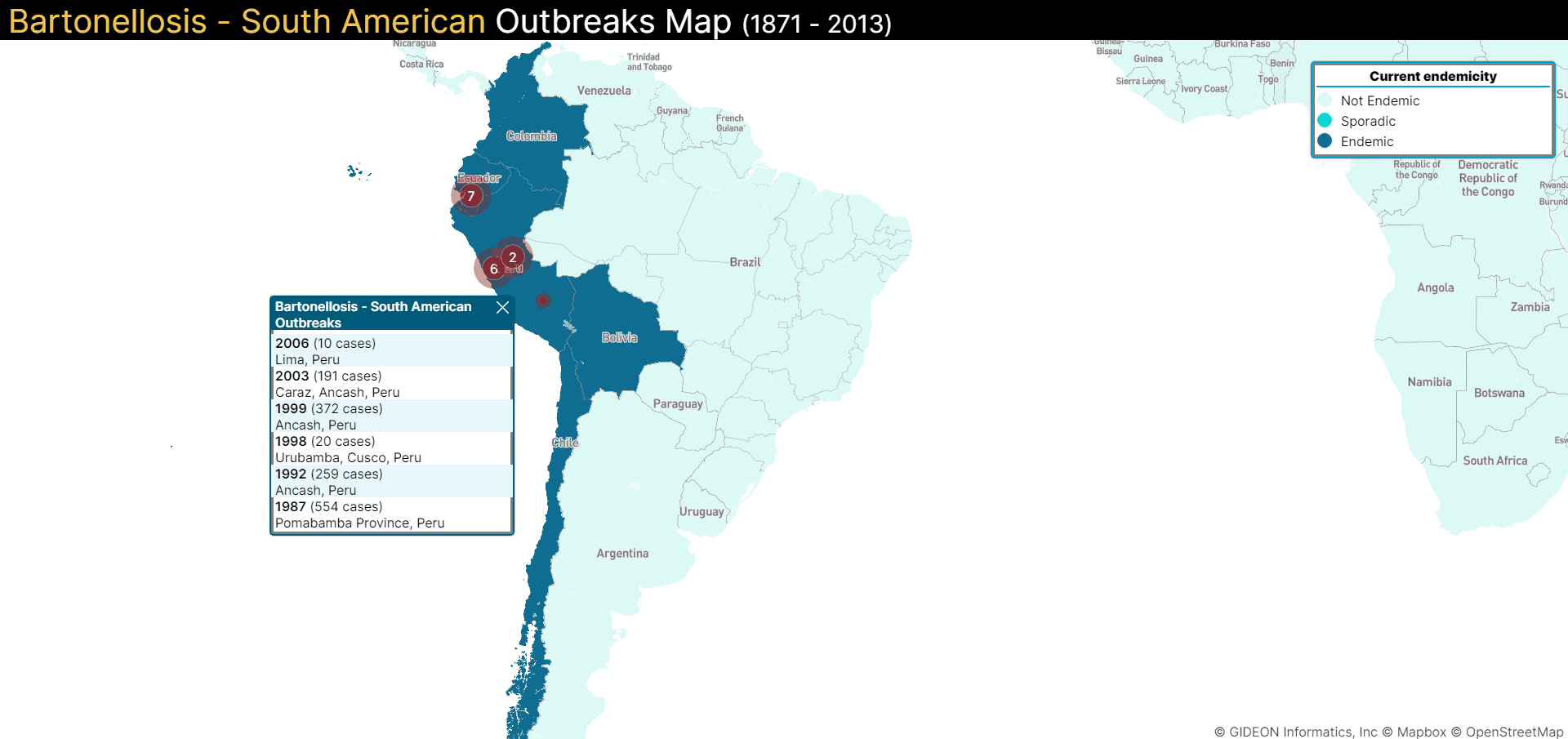

CSD has a global incidence of 6.4 cases per 100,000 adults and 9.4 cases per 100,000 children aged between five to nine years [1]. Incidence varies from place to place and depends on the regional population of fleas responsible for the transmission of the infection. Places that are warm and humid usually have more fleas and therefore have a higher incidence than arid areas (including mountain regions), where the disease incidence is much lower. Children between the age group of five to nine years are most affected [6].

How is it Spread?

Cat scratch disease is transmitted when an infected cat bites or scratches an individual. It can also spread when an infected cat licks an open wound on a person [7]. According to the CDC, approximately 40% of cats carry CSD in their lifetime, even though many remain asymptomatic. Kittens that are younger than one year are more likely to carry and transmit this disease.

Cats can get infected with CSD through flea bites and flea droppings. A cat that is infested with fleas may attempt to scratch or bite flea bites or the fleas themselves. At this time, infected flea droppings can get under their fingernails and between their teeth. The infected cat can scratch or bite a person and transmit the disease [3].

Biology

Endothelial cells that line the inner surface of the blood and lymphatic vessels are the primary hosts for B. henselae [8]. The bacteria also infect dendritic cells, epithelial cells, macrophages, and monocytes. CSD infections can cause cell damage and the growth of vaso-proliferative tumors in blood vessels [9].

Symptoms

The incubation period for cat scratch disease depends on the immunity levels of an infected individual but is usually around 3-10 days [7]. The following are some of the common symptoms:

- A small blister at the site of the scratch

- Fever

- Swollen or tender lymph nodes (within 1 to 2 weeks of infection)

- Eye infection

- Bone infection

- Spleen infection

- Brain infection

- Infection of the heart valves

- Liver infection [3].

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests for CSD include serology, PCR, and bacterial culture [10].

Treatment

When symptoms are mild, no treatment is needed — like if an infected individual presents with only swollen lymph nodes [3]. The antibiotic azithromycin effectively decreases swelling in lymph nodes, so it can be used in certain cases [3, 11].

In the case of neuroretinitis (inflammation in the eye), a combination of (200 mg/day) and rifampicin (600 mg/day) is given in combination for four to six weeks. For hepatosplenic (liver infection), rifampicine (20 mg/kg/day) alone or in combination with gentamicin (3 mg/kg/day) is given for four to six weeks [12].

Prevention

- Keep away from stray cats or kittens

- Avoid being scratched, licked, or bitten by cats or kittens

- Make sure that your cat or kitten is free from fleas

- Keep domestic cats away from stray cats

- People with a weak immune system are advised not to have a cat at home

- Wash your hands properly after handling cats [3]